King Edward VI's Defence of Astronomy

by Heather Hobden

Any writing on astronomy of more than 400 years ago is of some interest, and when the author is a person of historical notability that interest is increased. Thus the Defence of Astronomy by Edward VI has a particular fascination for us, not only for its content - for it is a competent account of the value seen in astronomy at that time - but also for the circumstances in which it was written.

|

Edward, son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, became King at the age of nine upon his father's death in January 1547. However, he took no active part in the government of the country until he was twelve years old. |  |

His education began at the age of three under Dr. Richard Cox, but in 1544, from the age of six, he was principally under the direction of John Cheke. Among his later exercises written for Cheke is the Defence of Astronomy, (Add.M.S.,BM.,4724, ff.104-6).

We shall describe here not only the contents of this unique dissertation but also something of its background.

It is appropriate to begin by saying a little about John Cheke and how he educated Edward. Cheke's primary responsibility was to educate the Prince in Greek and Latin. He was one of the excellent classical scholars of the age, having been the first Regius Professor of Greek at Cambridge. As a classical scholar he had, like others during the Renaissance, read for himself many of the Greek classical authors, and as well as being interested in the language of these works had taken much interest in their contents. It was in this way that classical learning had been rediscovered and among the subjects to benefit in this way astronomy featured prominently.

(It may be argued that the new astronomy of Copernicus' De Revolutionibus, published in 1543, but not generally accepted for several years, was basically the rediscovery of certain Pythagorean doctrines.)

Cheke's attitude towards the mathematical sciences is described by Richard Mulcaster, a contemporary of Edward, who stated,

"The worthy, and well learned gentleman Sir Iohn Cheeke, in the middest of all his great learning, his rare eloquence, his sownd iudgement, his graue modestie, feared the blame of a mathematicall head so litle in himselfe, and thought the prefession to be so farre from any such taint, being soundly and sadly studied by others, as he bewraid his great affection towards them most euidently in this his doing".(Johnson, F. R., Astronomical Thought in Renaissance England, New York, 1968).

Just as Cheke himself had gained knowledge of many subjects from his classical studies, so he ensured that his royal pupil also gained a wider knowledge by reading the classical authors at first hand. He told Roger Ascham, (his librarian and tutor to Edward's sister Elizabeth):

"I would have a good Student pass rejoicing through all Authors, both Greek and Latin; but that he will dwell in these few books only, First in God's Holy Bible, and then join with it Tully in Latin, Plato, Aristotle, Xenophanes, Isocrates and Demosthenes in Greek, must needs prove an excellent man". (Strype, John, The Life of Sir John Cheke, London, 1705).

A similar double purpose was involved in the setting of a number of exercises, of which the Defence of Astronomy is one, written for Cheke by the King from the age of eleven onwards.

Written in either Latin or Greek, these are discussions or arguments on set subjects, often of topical interest. They were all in the form of an oration or declamation, and are generally referred to as such. The oration on astronomy, although undated, was probably written in 1551, when the King was about thirteen.

In 1551 a brass quadrant (now in the British Museum) of Cheke's design, was made for Edward by Gemma Frisius. And also an astrolabe (which is now in in Brussels).

In 1551 a brass quadrant (now in the British Museum) of Cheke's design, was made for Edward by Gemma Frisius. And also an astrolabe (which is now in in Brussels).

Edward's portable writing desk is now in the Victoria and Albert museum. The photo was taken in the 19th century and given to us to use for this.

Edward's portable writing desk is now in the Victoria and Albert museum. The photo was taken in the 19th century and given to us to use for this.

(We were helped by amongst others by Beresford Hutchinson who helped with the photos of the quadrant etc.)

The oration on astronomy is in the form of a defence of that subject. The low esteem in which the mathematical sciences were generally held at that time is perhaps well illustrated by the quotation given above. Astronomy was no exception to this. At that time it was taken to include astrology, as well as what is understood as astronomy today. Thus astronomy at that time may not have been totally undeserving of the criticism that it received, but Edward was obliged to defend the whole subject.

The manuscript of the oration is written in Latin, in Edward's distinctive, if untidy, italic hand. The text had been reproduced in print in Literary Remains of King Edward the Sixth, by John Gough Nicols, London, 1857, but without an English translation.

So had translated it into English, making the translation as literal as possible in order to convey both the form and the style of the argument. Minor modifications (and additions shown in italics) have been made where this was necessary in order to produce a readable modern English text. The Latin text runs to some 900 words and the translation is longer. So some parts have been compressed in the version given here, but most of the text, including all of the more important arguments is given in full.

Edward did not give his oration a title, Nicols called it: Astronomiam utilem admodum esse Humano Generi. It reads as follows:

"Our ancestors considered it a most worthy thing to speak in defence of an innocent man, but though less of combatting evil things. The harder then is my task, for I support no mortal man, but a noble art and science, yet that science is often attacked and stands most in need of defence.

The art and science which, however, we now discuss is Astronomy. there are indeed those who hold it to be of use neither to the mind, nor to the body, nor to the state, which certain opinion it is necessary to treat with much censure, by no means undeserved. For what can be more foul than to say that knowledge that all, moved by divine instigation, seek and desire, is not useful or necessary to anything?

Knowledge, which is arisen from God, the source of all good, is divided into knowledge of the natural world, matters relating to discourse such as the arts of rhetoric and logic, and matters of ethics which apply to the morals of individuals and to the government of the State. What, in truth, is more natural than the knowledge of the elements, the heeavens, the stars, constellations and planets by whose motions our bodies, and also those of our subject animals, all plants, flowers and trees, the fruits of the earth, the vines and so on, are directed and ruled.

Being part of knowledge, arisen from God, who inspires us to investigate the natural world, Astronomy is certainly useful to man, for God does everything to some purpose.

The study of this art requires the greatest diligence and desire for knowledge, and sometimes a unique divine inspiration. No human being is himself so perfect that he may acquire knowledge of divine and heavenly things alone, and we can understand these things only with difficulty even with the help of books and teachers.

Let us therefore, consider earnestly the man who discovered the art of Astronomy, namely Seth, the son of Adam, who was a completely virtuous and dutiful man; and those who enriched it to great perfection, namely, the Egyptians and the Israelites, men indeed most learned, most educated, most wise, endowed with all kinds of learning and virtue. Do we then think that such men, so distinguished and wise as these, would have taken up such work for no account, but even should have been known to spend so much time, which is so valuable on it unless the subject were certainly useful? Or do we think that they were so far from humanity that if they had found the subject usefless or troublsome to the human race, they would have wished to promulgate it? By no means! Besides, I do not see how these people who are seen to despise and find no good in it are the equals in gravity, judgement, authority or learning of the ancients who studied that art, and who built schools and maintained teachers that others might be attracted to that study, and that many of their fellows might take it up. They themselves gave the greatest zeal to that work. Indeed, many schools were founded in Greece, not only by Princes, but also by free men, for the advancement of that art.

These things are well known to you and I hardly need point them out. Astronomy being one of the liberal arts belongs in the education of any young man. When so many have held Astronomy in great esteem how can anyone now criticise it?

The search for knowledge brings satisfaction to the mind. If this were a merely temporal subject it might five rise to some interest. But the heavens are permanent and the motions of the stars and planets most constant. No criticism of such a subject may be justified.

Yet all arts which propagate amongst men the glory of God are not lightly called useful. This indeed is the greatest good of man, that he comes to know God and depends on that knowledge. For Astronomy shows the work of God, through which he is realed to man. As David says in his Psalm "Coeli enim enarrant et patefaciunt coelemtem, invisibilem et immarcessibilem gloriam dei, atq orbis terrae suam potentiam".Paul likewise in the first chapter of his epistle to the Roman people says that although they do not yet know God perfectly, they may come to know thim through his works. The more then we get to know Astronomy the more wonderful will we see God's work to be.

Further, since the greatest states consist in large part of merchants and farmers, Astronomy in benefitting these brings no little profit to the state. The farmer, for instance, knowing the seasons which will probnanly be calm and which others will be stormy may conveniently sow, plough, reap and harvest the land whenever the days are most propitious; through the ignorance of Astronomy and other similar arts many crops are consumed by storm, rain, thunder and even drought, and are lost. The merchant, in truth, without knowledge of the stars is in no way able to navigate or steer his ship correctly. All these men indeed sail their ships according to the motion of the stars.

Wherefore, since all knowledge is of nature, and is the gift of God implanted in human hearts, since the abilities of the discoverers and propagators of Astronomy have been God-given, since if it be one of the liberal arts it will demonstrate truth and give satisfaction to the enqiring mind wishing all things to know, since again it is useful to farmers and merchants, showing the glory of God to the whole world, we think it far from useless to the body, the mind and the State.

This have I said."

That then is what Edward wrote, but it needs some explanation. The declamation is a good account of the importance seen for astronomy in mid-sixteenth century England - a few years before the invention of the telescope. The major part of the argument is theological in nature. This was important at that time, although it is not the type of argument to be axpected today. Although astronomy was criticised on several grounds at that time, the part of the subject most vehemently attacked was what is known as judicial astrology. this is the part of astology that claims to predict men's future lives and actions. It was thus considered by many to be in direct opposition to the Christian doctrine of free will. Thus Edward, who like most of his time had some belief in astrology, seems careful to say that the motions of the stars and planets rule only our bodies leaving our minds presumably free.

The idea that astronomy consitutes knowledge given from God is repeated several times. Thereby we are expected to see the nature of God more clearly, for which purpose all knowledge is given to us. And, of simple necessity, anything given by God must be useful.

Apart from theological arguments the weight of classical interest in astronomy may be brought to bear. The ancients, who are implicitly assumed superior to sixteenth-century man, would not have studied the subject without good reason. Finally, the application of astronomy to everyday life are mentioned in its support.

Thus Edward is able to prove that astronomy benefits the mind - since spiritual advantage may come from knowledge of astronomy, - the body - though astrology - and the State - as farmers and merchants make use of astronomical knowledge. (You may have noticed this included the weather - anything above the Earth's surface was then in the realm of astronomy.)

The argument is not wholly medieval in form, yet it is hardly "modern", and most of the arguments would be considered irrelevant or invalid now. But it is as a statement of the orthodox view of the time - being as much Cheke's opinion as Edward's - that the declamation is of value to the historian of astronomy; and it is as the work of a King that it is of particular interest.

Although the content of the declamation on astronomy is in essence unoriginal, we should be doing Edward less than justice if we left the impression that he was not able to think for himself on this subject.

This is shown in his audiences with the famous Italian mathematician and physician, Gerolamo Cardano.

Cardano had been in Scotland at the invitation of John Hamilton, Archbishop of St. Andrews, who hoped Cardano might be able to cure his asthma. (Cardano had acquired a reputation for curing lung diseases).

Cardano had been in Scotland at the invitation of John Hamilton, Archbishop of St. Andrews, who hoped Cardano might be able to cure his asthma. (Cardano had acquired a reputation for curing lung diseases).

Anxious to avoid another long voyage in a smelly French galley (the chained galley slaves had to relieve themselves where they sat), Cardano returned south overland, on "an ambling good-tempered horse" to London, where John Cheke had invited him to stay.

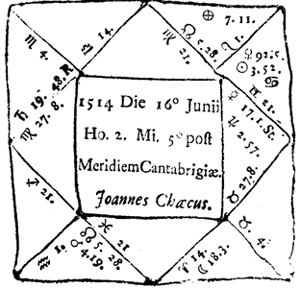

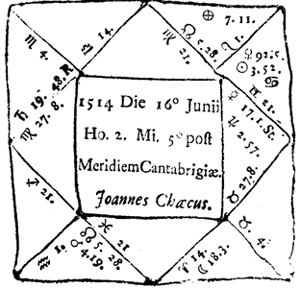

Cardano cast Cheke's horoscope and Cheke arranged for him to see the King, and dedicate his new book "De Varietate Rerum" ("On a Variety of Things") to the King.

This was at the end of October 1552. Edward had been ill with something spotty (he says measles and smallpox in his journal) a few months earlier, but had recovered and gone on a long progress around the south of his country. Cardano had no way of knowing, when he cast his horoscope at the request of the King's Council, that the fifteen year old King would be dead next summer. Which was just as well.

Edward asked Cardano (in Latin) about his book. Cardano answered "In the first chapter I show the cause of comets, long sought for in vain." "What is it?" asked Edward. "The concourse of the light of the planets" said Cardano.

This perplexed Edward - and it may perplex you. But at this time, the universe was still conceived of as a solid model with the heavenly bodies fixed to solid transparent spheres rotating about the Earth fixed in the centre. With the heavens solid from the Moon upwards - the only changes could occur in the Earth's atmosphere beneath the Moon's sphere. And it was only here, near the Earth, that solid bodies could fly through, since the rest of the universe was solid.

Hence the problem with comets. For although the astronomical telescope was still a few years off, other astronomical instruments had improved. And measurements of the parallax of what we now know as "Halley's Comet" recorded by Peter Apian in 1531, had shown it to be orbiting the sun, therefore moving above the orbit of the moon.

So there was now a problem with the nature of comets. Which Edward was already aware of. He asked Cardano "How is it, since the motions of these are different, that the light is not scattered, or does not move in accordance with their motion?" Cardano replied, "It does so move, only much faster than they, on account of the difference of aspect, as the Sun shining through a crystal makes a rainbow on a wall. A very slight movement of the crystal makes a great change in the rainbow's place." "And how can that be done" asked Edward, "when there is no subject? For to the rainbow the subject is the wall." "It occurs as in the Milky Way" said Cardano, "and by the reflection of lights."

Cardano left for Milan, by way of Dover where he paid for a 12 year old boy called William, used him as rent boy, and added him to his family of three children - none of them well-behaved either.

Cardano sent back the King's horoscope, foretelling of a long life beyond 56 years, crammed with a vague list of virtues and wisdom. Complete rubbish of course. And Edward was dead and leading members of his Council beheaded, by the time it arrived. But no 16th century astronomer could survive without the fees for horoscopes. And Cardano back with his dreadful family, his gambling and disputes with other mathematicians was a safe distance from the events in England.

The original manuscript of King Edward VI's Defence of Astronomy can be seen in the British Library.

More on astronomy in the reign of Edward VI on the website about Lady Jane Grey's Clocks.

This webpage was added and updated from material originally collected for a paper written by Brian Hellyer and Heather Hellyer (now Hobden) published in the Journal of the British Astronomical Society in 1972. It is based on original research by Heather Hobden. The manuscript was copied for us, by the British Library with permission to use it in publications.

| This website written, designed and maintained by Heather Hobden | | The Cosmic Elk |

|

copyright Heather Hobden and The Cosmic Elk

In 1551 a brass quadrant (now in the British Museum) of Cheke's design, was made for Edward by Gemma Frisius. And also an astrolabe (which is now in in Brussels).

In 1551 a brass quadrant (now in the British Museum) of Cheke's design, was made for Edward by Gemma Frisius. And also an astrolabe (which is now in in Brussels). Edward's portable writing desk is now in the Victoria and Albert museum. The photo was taken in the 19th century and given to us to use for this.

Edward's portable writing desk is now in the Victoria and Albert museum. The photo was taken in the 19th century and given to us to use for this. Cardano had been in Scotland at the invitation of John Hamilton, Archbishop of St. Andrews, who hoped Cardano might be able to cure his asthma. (Cardano had acquired a reputation for curing lung diseases).

Cardano had been in Scotland at the invitation of John Hamilton, Archbishop of St. Andrews, who hoped Cardano might be able to cure his asthma. (Cardano had acquired a reputation for curing lung diseases).